Biophotonics for brain imaging is the optic of this blog article.

Introduction: The Photonic Revolution in Neuroscience

In the past two decades, the human brain has transitioned from being a “black box” of electrical activity to a dynamic optical landscape, illuminated by advances in biophotonics. This field, the convergence of light and biology, is redefining how researchers visualize, stimulate, and communicate with neural tissue.

While optogenetics opened new horizons by using genetically modified neurons that respond to light, it also exposed inherent limitations, such as genetic invasiveness, limited depth penetration, and difficulty in translating to human use. As a result, scientists and engineers are increasingly looking beyond optogenetics, developing next-generation photonic interfaces and imaging modalities that promise higher precision, non-invasiveness, and scalability.

Biophotonics for brain imaging and neurointerfaces is no longer confined to laboratories. With innovations in near-infrared (NIR) lasers, fiber optics, metasurfaces, and implantable photonic chips, the field is quickly advancing toward clinical translation, where light may soon play a pivotal role in diagnosing and treating neurological disorders.

Optical Windows to the Brain

For light to interact effectively with neural tissue, it must navigate the brain’s natural scattering and absorption barriers. The so-called biological optical window, typically from 650 to 1350 nm, represents the sweet spot where light can penetrate several millimeters to centimeters into soft tissue.

Within this range:

Red and NIR light experience minimal absorption by hemoglobin and water, allowing for deep imaging and gentle stimulation.

Shorter wavelengths (400–600 nm), while providing high resolution, are limited to superficial cortical layers due to scattering.

Longer MIR wavelengths (>1500 nm) can deliver localized heating or stimulate neuronal membranes through thermal gradients, forming the basis for infrared neural stimulation (INS).

This optical insight has driven the design of advanced lasers, fiber-optic probes, and scattering-compensation algorithms that allow researchers to reach deep brain regions with micrometer precision, all while minimizing invasiveness.

Biophotonics for Brain Imaging: Advanced Imaging Modalities

Biophotonics has transformed brain imaging from static snapshots to dynamic, high-resolution views of living neural circuits. Several complementary modalities have emerged as the backbone of modern neurophotonics.

Two-Photon and Three-Photon Microscopy

These nonlinear imaging techniques use pulsed femtosecond lasers to excite fluorophores only at the focal point, drastically reducing background noise. Two-photon microscopy allows imaging several hundred microns deep into cortical tissue, while three-photon microscopy extends this to over a millimeter, enough to visualize neuronal networks across entire cortical columns. These methods are vital for observing neural activity, synaptic plasticity, and real-time neurotransmission.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

Originally developed for ophthalmology, OCT now serves as a label-free tool for imaging microvasculature and cortical structure. By analyzing light backscatter, OCT provides cross-sectional images of brain tissue with micron-scale resolution, essential for studying stroke dynamics and neurodegenerative progression.

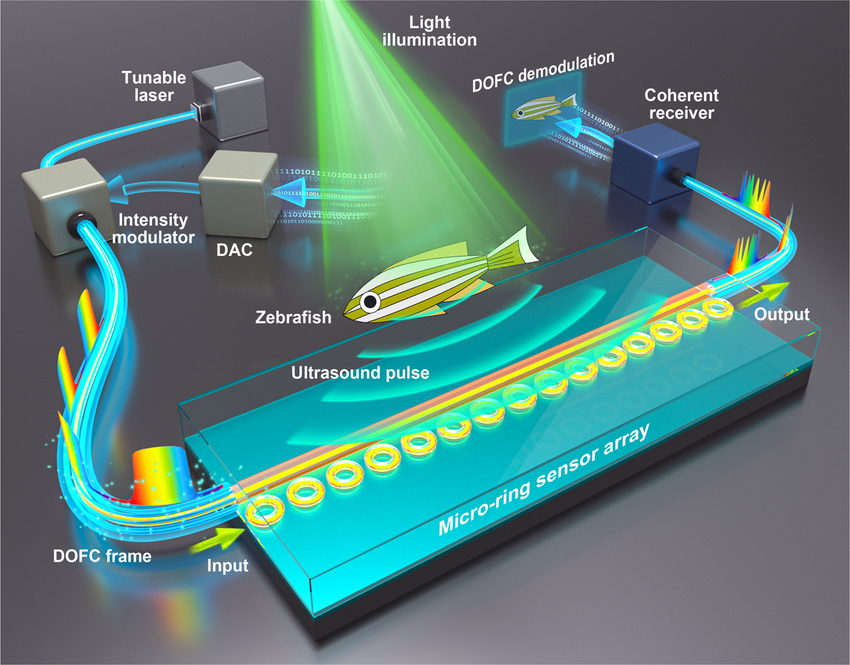

Photoacoustic Imaging

In photoacoustic tomography (PAT), pulsed laser light induces ultrasonic waves in absorbing tissues, combining optical contrast with acoustic depth penetration. This hybrid modality enables real-time mapping of oxygenation, hemodynamics, and metabolic changes – key parameters for understanding functional brain states.

A schematic of photoacoustic tomography (PAT) – courtesy of Nature Communications

Diffuse Optical Tomography (DOT)

DOT and its real-time variant, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), are gaining traction as non-invasive tools for monitoring cerebral blood flow and oxygenation. While their resolution is lower than that of microscopy, their ability to probe the brain safely through the skull makes them ideal for clinical and wearable neuroimaging systems.

Table: Comparison of Optical Brain Imaging Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Photon Microscopy | Uses near-infrared femtosecond pulses to excite fluorophores via nonlinear absorption. | – High spatial resolution (submicron) – Reduced phototoxicity – Imaging up to ~600–800 µm deep | – Requires fluorescent labeling – Slow frame rates for large areas – Expensive ultrafast laser systems |

| Three-Photon Microscopy | Extends 2PM with longer wavelengths (e.g., 1300–1700 nm) and triple-photon excitation. | – Deeper penetration (up to ~1.2 mm) – Excellent signal-to-noise ratio – Enables imaging of deep cortical layers | – Requires higher laser power – Limited availability of compatible dyes – Increased thermal effects risk |

| Optical Coherence Tomography | Measures backscattered light to reconstruct tissue microstructure. | – Label-free imaging – High axial resolution (1–10 µm) – Real-time acquisition | – Shallow penetration (<2 mm) – Limited contrast for neural activity – Sensitive to motion artifacts |

| Photoacoustic Tomography | Converts absorbed light into ultrasound signals for deep imaging. | – Deep penetration (up to several cm) – Combines optical contrast with acoustic resolution – Visualizes hemodynamics & oxygenation | – Limited temporal resolution – Complex reconstruction algorithms – Bulky instrumentation |

| Diffuse Optical Tomography / fNIRS | Uses multiple NIR sources and detectors to map hemoglobin absorption. | – Non-invasive and portable – Safe for human use (through skull) – Good for monitoring blood flow & oxygenation | – Low spatial resolution (~1 cm) – Limited to cortical surface – Susceptible to motion and ambient light noise |

| Widefield / Epifluorescence Microscopy | Illuminates and collects emission from a broad area. | – Fast and simple – Suitable for population-level imaging – Inexpensive setup | – Low depth penetration (<200 µm) – High background fluorescence – Photobleaching risk |

Neurointerfaces: Light as a Neural Communication Medium

While traditional brain–machine interfaces rely on electrical electrodes, photonic neurointerfaces offer a fundamentally different approach. Instead of injecting current, they use precisely controlled light to stimulate, inhibit, or record neural activity.

Infrared Neural Stimulation (INS)

INS exploits rapid, localized heating of neural membranes induced by pulsed infrared light (typically 1.8–2.1 µm). This transient thermal gradient can depolarize neurons without genetic modification. Because it is contactless and selective, INS holds strong promise for cochlear prosthetics, retinal stimulation, and peripheral nerve interfaces.

Plasmonic and Nanoparticle-Assisted Stimulation

Gold and carbon-based plasmonic nanoparticles can convert absorbed light into localized heat or electric fields. When targeted to specific neuron populations, they enable ultrafast, nanoscale optical control of brain regions. Researchers are exploring these for minimally invasive neurotherapies and localized drug delivery systems.

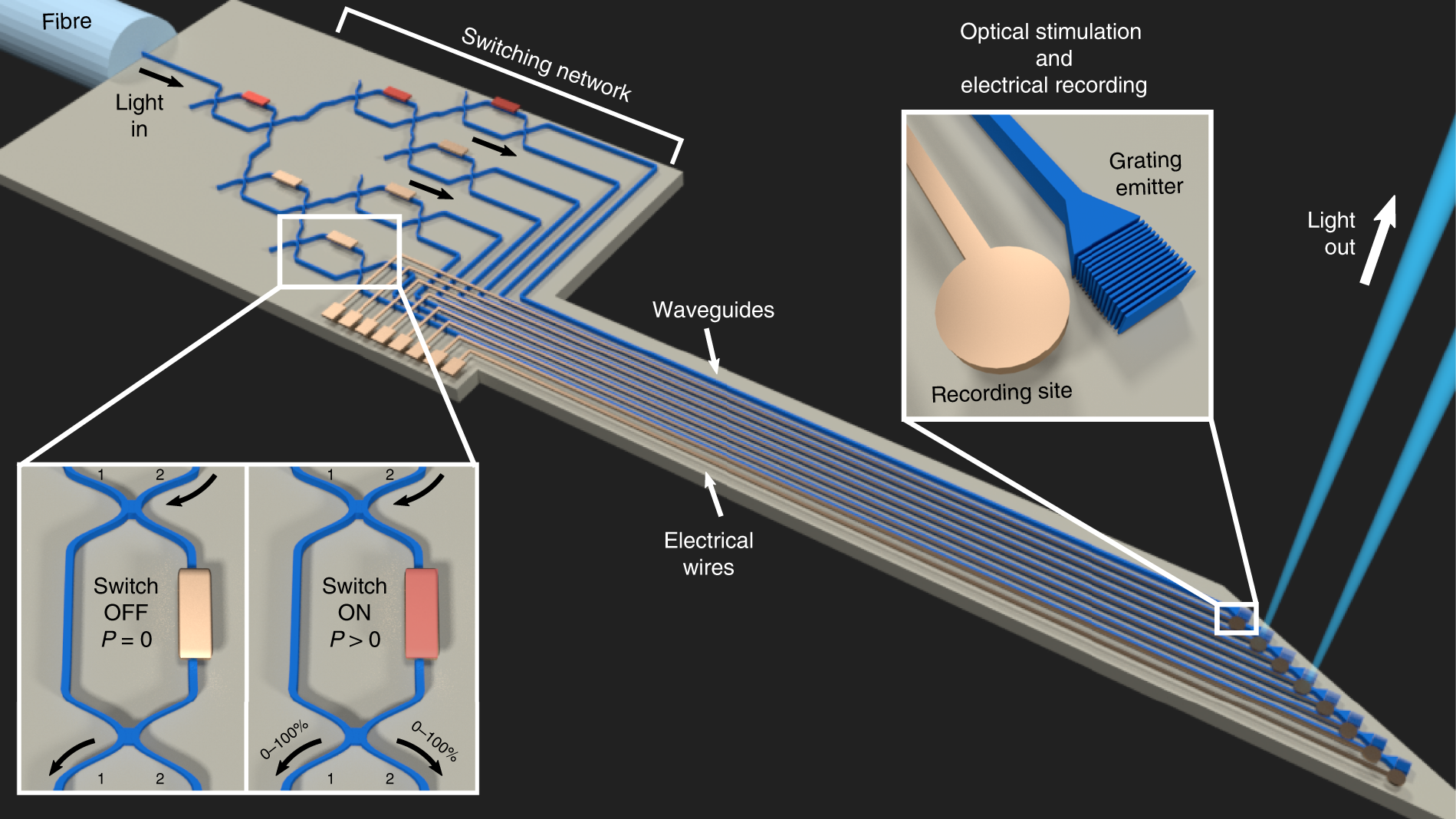

Implantable Photonic Probes

Advances in fiber optics and micro-LED arrays are paving the way for flexible, miniaturized brain implants further advancing the field of biophotonics for brain imaging. These photonic probes can deliver patterned light deep into neural tissue with micron-scale precision. Emerging silicon photonic chips integrate multiple waveguides, detectors, and light sources on a single platform, enabling closed-loop optical stimulation and sensing.

Nanophotonic silicon probes for deep-brain optical stimulation (Courtesy of Nature Photonics)

Hybrid Photonic-Electronic Systems

The frontier of neurotechnology lies in hybrid interfaces that merge optical readout with electronic feedback. Systems combining photonic sensors with CMOS electronics can detect calcium transients, membrane potentials, or metabolic shifts in real time bridging the gap between brain signals and artificial intelligence algorithms.

Emerging Materials and Techniques

The success of biophotonic neurointerfaces depends heavily on materials that are biocompatible, transparent, and mechanically soft enough to integrate seamlessly with neural tissue.

Silicon Nitride and Polymer Waveguides: These materials allow low-loss light transmission in the visible-to-NIR range while maintaining flexibility suitable for implantable devices.

Hydrogel-Integrated Optics: Hydrogels mimic brain tissue elasticity and can encapsulate photonic circuits or nanoparticles, minimizing immune responses.

Quantum Dots and Fluorescent Indicators: Advanced optical probes like voltage-sensitive dyes and genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) extend the temporal resolution of optical readouts, enabling millisecond-scale mapping of action potentials.

Near-Infrared Sensors: By moving detection into the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), researchers are achieving deeper tissue imaging with reduced scattering and autofluorescence.

In parallel, nanophotonic metasurfaces are being engineered for miniature lensing and beam shaping, enabling compact brain-imaging devices that may one day fit into wearable neurocaps or cranial implants.

Applications and Emerging Frontiers

The implications of these technologies reach far beyond fundamental neuroscience. Biophotonic systems for the brain are already finding roles in medical diagnostics, neuroprosthetics, and even human–computer communication.

1. Neurological Diagnostics and Monitoring

Optical methods like fNIRS and photoacoustic tomography are being integrated into portable devices for bedside monitoring of cerebral oxygenation and hemodynamics. These tools could provide real-time insight during stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury, or surgery without the need for bulky MRI or invasive electrodes.

2. Neuroprosthetics and Rehabilitation

Photonic interfaces have the potential to restore lost sensory or motor function by stimulating neural pathways with light. Early prototypes of optical cochlear implants and infrared-stimulated muscle interfaces demonstrate promising results for patients with hearing loss or motor impairment.

3. Brain–Computer Interfaces (BCIs)

Optical BCIs could surpass traditional electrical ones by offering higher spatial resolution and lower noise. By detecting functional signals such as oxygenation or calcium flux, photonic BCIs may enable new forms of communication for paralyzed patients and enhance cognitive-state monitoring in human–machine collaboration.

4. Mental Health and Neuromodulation

Light-based neuromodulation could one day offer personalized, non-invasive treatments for depression, anxiety, and epilepsy. By combining photonics with AI-driven signal analysis, future systems could automatically detect and correct pathological brain activity in real time.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

With the growing ability to read and influence the brain optically comes a responsibility to address ethical, safety, and privacy concerns. The long-term effects of chronic optical stimulation, potential overheating, and unintended signal manipulation remain under study. Additionally, the integration of biophotonic BCIs with AI raises questions about data security and cognitive autonomy.

Developing transparent standards, robust safety protocols, and ethical frameworks will be critical to ensuring that these technologies serve both scientific discovery and human well-being.

Conclusion: Lighting the Path Forward

Biophotonics has already revolutionized how we visualize and interact with the living brain, but the journey beyond optogenetics has only just begun. With innovations in infrared stimulation, metasurface imaging, and photonic neurointerfaces, researchers are approaching a future where light not only reveals neural activity but also restores and enhances brain function.

The convergence of photonics, materials science, and neuroscience is ushering in a new era of optical neurotechnology, one that may ultimately allow light to communicate directly with thought itself.

Further Reading

Yuste, R., & Church, G. M. (2014). The new age of optical neurotechnologies. Neuron, 83(6), 1232–1250.

A foundational review on how optical tools are transforming neuroscience, from imaging to control.Kim, C. K., Adhikari, A., & Deisseroth, K. (2017). Integration of optogenetics with complementary methodologies in systems neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(4), 222–235.

A comprehensive look at optogenetics and its integration with modern imaging and stimulation techniques.Xu, C., & Denk, W. (2023). Advances in multiphoton microscopy for deep brain imaging. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 46, 1–25.

A current overview of two- and three-photon microscopy technologies enabling deep-tissue visualization.Chen, T. W., et al. (2013). Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature, 499(7458), 295–300.

Seminal paper introducing high-performance calcium indicators for optical mapping of brain function.Izzo, A. D., et al. (2018). Infrared neural stimulation: A new modality for neural activation. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 735.

Discusses mechanisms and applications of infrared neural stimulation as a non-genetic alternative to optogenetics.Choy, C. J., et al. (2022). Biophotonic interfaces for neural activity recording and stimulation. Advanced Materials, 34(15), 2108707.

An in-depth review of implantable photonic probes and materials used in neural interfacing.Hong, G., Antaris, A. L., & Dai, H. (2017). Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 1(1), 0010.

Explores NIR-II wavelength imaging for deep-tissue, low-scattering brain visualization.Pavone, F. S., & Sacconi, L. (2017). Optical neuroimaging: From the synapse to the whole brain. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, 23(3), 6800810.

Reviews advances in neurophotonics, including photoacoustic and holographic imaging.Qian, Y., et al. (2022). Optically controlled neuromodulation using plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano, 16(5), 7271–7284.

Discusses nanoparticle-assisted light stimulation for localized, minimally invasive neural activation.Heo, C., et al. (2023). Hybrid optoelectronic systems for high-resolution brain–computer interfaces. Nature Communications, 14, 4621.

Describes emerging photonic–electronic hybrid devices for real-time brain communication and data processing.